Closing the other gap: instilling Indigenous knowledge in young hearts and minds

Meaningful engagement with Indigenous knowledge in education is vital for reconciliation.

Meaningful engagement with Indigenous knowledge in education is vital for reconciliation.

Nadia Razzhigaeva

UNSW Arts Design & Architecture News & Content Coordinator

02 9348 1229

n.razzhigaeva@unsw.edu.au

Researchers from the UNSW School of Education are engaging with local Indigenous communities to address a critical knowledge gap around First Nations people and cultures in schools.

pursues social justice through research into equity in education, addressing intersectional disadvantage across race and gender. Together with UNSW Scientia Indigenous Research Fellow Associate Professor Kevin Lowe, she advocates for teaching policies and practices and a culturally responsive curriculum that improves Indigenous educational outcomes.

“If we want to close the knowledge gap around Indigenous culture, we need to prioritise life-long learning around, and appreciation of, Australia’s shared history,” Dr Amazan says.

Introducing Indigenous knowledge to our children’s education in authentic ways is vital for Reconciliation, Dr Amazan says.

“Research shows that partnerships between schools and Indigenous communities, and the embedding of Indigenous cultural knowledge and perspectives in schools, can improve schooling for all students,” Dr Amazan says.

“Every child across this vast continent deserves to learn from the wisdom of the first custodians of the country they live on,” says A/Prof. Lowe, a Gubbi Gubbi man.

“This way, the next generation will be equipped to make better decisions that impact the lives of First Nations peoples.”

The researchers are collaborating on the , which aims to address the systemic issues that disadvantage First Nations people in education.

This project identifies the critical role of school leadership, cultural engagement and authentic community partnerships in uplifting Indigenous student learning trajectories. It adopts a micro-treaty model between communities and schools for shared accountability.

“We’re working with [eight] schools to establish Aboriginal language and cultural programs that really sing to the heart of communities about their sense of Aboriginal identity,” A/Prof. Lowe says.

Research has shown that reinforcing Indigenous students’ cultural identities at school improves their performance overall, A/Prof. Lowe says.

“We know from the research that students who feel connected culturally to school become connected to school educationally. And so, our task is to help students be able to live more successfully between two worlds.”

The program, which includes ‘Learning from Country’ immersion experiences, curriculum and pedagogic workshops, professional learning conversations and cultural mentoring, addresses gaps in teacher knowledge and develops the skills for cultivating profound relationships with Indigenous students.

Additionally, A/Prof. Lowe is conducting research on policy analysis, survey and qualitative research to identify the barriers to successfully teaching Indigenous content in the curriculum.

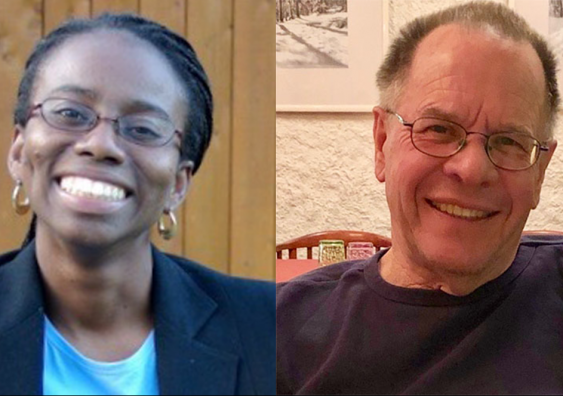

Dr Rose Amazan and A/Prof. Kevin Lowe are part of a team leading the Culturally Nourishing Schooling project which aims to address the systemic issues that disadvantage First Nations students. Photo: Supplied.

Read more:

The researchers are also collaborating on the , which raises awareness of and respect for Australia’s First Nations people and culture through primary education.

The project embeds members of local Aboriginal communities within schools to act as cultural educators, working with teachers to integrate Aboriginal histories, knowledge and cultures across the curriculum.

The project will provide a proof-of-concept for Know your Country, a nationwide advocacy campaign convened by World Vision to place a First Nations cultural educator in every Australian primary school. The campaign is supported by research from the UNSW Matraville Education Partnership, established in 2015, which promotes educational advancement and opportunity through teacher development, student initiatives and community involvement.

Dr Scott Winch, Wiradjuri man and World Vision Australia First Nations senior policy advisor, says it’s time for change.

“The campaign urges education ministers, systems and schools to hold space for local First Nations communities,” he says. “Australians support change. In our research, 74 per cent of our survey respondents said they believe education is important in reducing racism, and 62 per cent agreed the government should do more to reduce racism in the education system.”

The three-year project, in partnership with the NSW Aboriginal Education Consultative Group (AECG), involves whole classes and year groups and is a hands-on approach.

Cultural educators cook food (damper and johnny cakes), perform smoking ceremonies, discuss artefacts, create artworks, and share stories of the Dreaming, local history and their lives with the children. They also emphasise truth-telling, sharing their personal and community experiences of issues such as mission life, racism, and the Stolen Generations. Teachers work closely with Cultural Residents to find deep and engaging ways to link their knowledge and expertise to the school curriculum.

Aunty Maxine Ryan, cultural educator at the Little Bay Community of Schools, says the students are “fascinated”. In one exercise, they create and share family trees.

“Their stories are just as important as my story,” she says. “Because that’s what reconciliation’s about. Australia is a multicultural country.”

Aunty Maxine grew up on the gated mission at La Perouse in the 1950s. Access to education was precarious: as late as the 1970s, Aboriginal children could be excluded from school at the request of teachers and parents.

Schools are not seen as safe by many Aboriginal people, Aunty Maxine says. “We didn’t grow up with books. We weren’t allowed to go to the library. We weren’t allowed to learn.

“That’s why today, because nine times out of 10 the older people at home – they can’t read. And this is what we teach in the schools, is to realise that a child’s not going to say, but mum and dad can’t read.”

Through greater cultural awareness, the project promotes a more inclusive learning environment. Additionally, it forges connections with local communities, inviting parents into schools, making them feel welcome, perhaps for the first time.

“A lot of Aboriginal parents and grandparents never went to [one of the schools I worked in]. But [when we celebrated National Reconciliation Week], they were there. They’ve seen that gate open,” Aunty Maxine says.

Aunty Maxine Ryan, a local Dharawal woman from La Perouse, works as a Cultural Resident in four schools in Sydney's eastern suburbs. Photo: Supplied.

Engaging Indigenous communities in education gives them much-needed agency in the teaching of Australia’s history, Aunty Maxine says.

“I want my voice to be there. I want all Aboriginal people to have a voice. I want all Aboriginal children to have a voice. And I’m passionate about my culture. And I’m passionate about teaching, and [about] this young generation learning,” she says.

While Indigenous perspectives are present across disciplines, few teachers feel equipped to teach them in a meaningful way, Dr Amazan says. Engaging with cultural educators helps them reconceptualise the way they teach this content beyond mere tokenism, she says.

Aunty Maxine says the response from teachers is overwhelmingly positive: “They just want more and more.”

The Cultural Residents project is gathering data on benefits, determining the best structure and governance models, and creating an online toolkit to aid other schools and communities that want to engage a Cultural Resident.

For Aunty Maxine, the work connects her to her elders, who always hoped to help incorporate Indigenous culture in schools. “This is where our mums started, and it’s like somebody brought us here to keep it going,” she says.

“And this project now, that we’re doing, we’re just keeping that flowing, and putting more stories in... And to think that this is there now [for students and schools, and that] it’s real for them – well, we get a little bit teary-eyed.”