Stampedes, sharks and cyclones: uncovering the adventures behind 50 years of coastal research

A new collection of coastal research fieldwork stories reveals the exciting – and sometimes life-threatening – tales behind the science.

A new collection of coastal research fieldwork stories reveals the exciting – and sometimes life-threatening – tales behind the science.

Sherry Landow

News & Content Producer

(02) 9065 4039

s.landow@unsw.edu.au

Rob Brander had both hands pushed against the wall of his tent in a fight against the gale-force winds of the mini-cyclone raging outside.

It was February 1992 – early in his career as a coastal scientist – and he’d been helping colleagues conduct their fieldwork on the remote Nine Mile Beach in Central Queensland. The storm had come on suddenly, and the nearest town was a two-hour 4WD drive away. The team’s only option was to take shelter.

The rain outside wasn’t just torrential, but horizontal. The thunder was deafening. A flash of lightning illuminated a herd of cattle stampeding across the beach, but the researchers didn’t have time to soak in – or even question – that bizarre sight now. They were busy using their combined body weight to keep the tent upright.

A gust of wind suddenly picked up the front of the tent, taking it – and the researchers – fully airborne. The researchers were thrown on their backs metres away, while the roof was cleanly ripped off.

“As a field scientist, you’re completely at the mercy of the conditions,” says , now a coastal geomorphologist at UNSW Sydney. “You can plan the best experiment, but there’s a lot of luck involved when you’re out on the field – both good and bad.”

The research team's office – and home – during the Nine Mile Beach field trip. The main research tent survived the storm, but two of Prof. Brander's colleagues needed to camp under the 4WD after their sleeping tent was blown away. Photo: Rob Brander.

The Nine Mile Beach trip is one of the many field research memories captured in ‘’, a special issue of the that looks back on 50 years of research from coastal scientists around the world. Prof. Brander co-edited the special issue with Professor Andy Short, a coastal geomorphologist at the University of Sydney and his former PhD supervisor.

Unlike most scientific journals, this edition isn’t just about the science, but the tales of getting the science. Each story is filled with funny, uncanny or life-threatening moments – and sometimes all three.

“When I started doing fieldwork in the 1980s, it took a lot of time – sometimes months – to get the data. You would put your instruments in the water and wait for the right conditions,” says Prof. Brander.

“To fill the time, the older researchers shared all these incredible stories about past fieldwork. Scientists that I read about in textbooks and seminal papers turned into near mythical figures. It became a kind of fieldwork lore.”

Now, improvements to technology mean that instrument data is available almost immediately. While these advancements have made field trips more efficient, the evenings can be taken up analysing the data instead of storytelling.

“I felt that we were losing a part of coastal fieldwork history,” says Prof. Brander. “This special issue became my passion project.

“Scientific fieldwork often involves extreme locations and conditions. Wild, bizarre and unexpected stuff happens, but at the same time significant scientific advances occur. I wanted to capture that.”

Prof. Brander (right) setting up an instrument pod with colleague Gerd Masselink. Photo: Rob Brander.

The mini-cyclone didn’t end the Nine Mile Beach research trip. In the following days, Prof. Brander would find himself swimming away from a shark, being threatened by a gun and pet dingo, and in hospital with a tropical ulcer.

Despite all that, he would eagerly volunteer for the next field trip just a few months later.

“It becomes addictive,” says Prof. Brander. “Both the physical and scientific challenge. Some people just thrive on it.”

Prof. Brander always knew he wanted to work outdoors, but it wasn’t until hearing his first-year physical geography lecturer talk about fieldwork that he considered a career in coastal research.

“I remember thinking it sounded awesome, so I asked my professor if he hired students,” Prof. Brander says. “He said yes, but only if I got my SCUBA diving license.”

Soon after, Prof. Brander became a diver for coastal experiments. He lived and studied in Canada at the time and would need to dive in cold water – sometimes as chilly as eight degrees Celsius – for up to six hours a day, every day, for weeks on end.

The conditions didn’t scare Prof. Brander off a life of coastal research. Instead, they motivated him to move to the warmer climes of Australia, where his 1990s standard work uniform became speedos and a hat.

Eating donuts while doing donuts: Prof. Brander (right) and his colleague Phil Osborne found ways to keep entertained in between freezing cold dives off Prince Edward Island. Photo: Rob Brander.

Field researchers need to be quick thinkers to overcome any problems that arise, says Prof. Brander. They also need to have a lot of practical skills that aren’t usually in the job description, like resourcefulness and tech-savviness.

“Equipment sometimes fails, so you might need to figure out how to rewire instruments to stop the whole experiment failing,” he says.

The most impressive field innovation Prof. Brander ever saw happened during the Nine Mile Beach experiment. The beach had extreme high and low tides (called ‘macrotidal’), which meant that the underwater equipment was frequently exposed to air throughout the day.

“One of the problems with the flowmeters was that the impellors [rotors] would spin madly in the wind when exposed, which could quickly wear out the bearings,” he writes in the special issue.

“Dave Mitchell [a field technician] placed children’s Tiny Teddy biscuits in the impellors when they became exposed, stopping them from spinning. The biscuits would dissolve when the sensors next became submerged and the flowmeters would start measuring again. Sheer genius.”

Quick thinking on the field – and a sacrificed snack – helped stop the flowmeter rotors from spinning in the wind and wearing out the bearings. (If you look closely, you can see a teddy poking out of the top rotor.) Photo: Ian Turner.

At other times, skills in persuasion and tact can come in handy for managing human threats.

On the researchers’ last day at Nine Mile Beach, a group of miners camping nearby wanted to commandeer their supplies. The miners started circling the camp in their 4WDs, shooting their gun into the distance and threatening the group with their pet dingo.

“The whole situation felt like something out of Apocalypse Now, or even worse, Deliverance,” Prof. Brander writes. “I thought we were goners.”

They were talked out of the situation by PhD candidate , who is now a professor at UNSW Engineering.

“Ian … handled it beautifully. He was exchanging all the right banter, having a laugh, it even looked like he was enjoying himself. It was an impressive tour de force that may have saved our lives…”

Prof. Turner, who now runs UNSW’s Water Research Laboratory, remembers just feeling determined to leave.

“I was simply relieved we were at the end of a long and challenging fieldtrip,” he says.

“A few blokes with guns and a dingo somehow paled into insignificance at the time, compared to the prospect of packing up and leaving the next day. Nothing was going to stop that happening.”

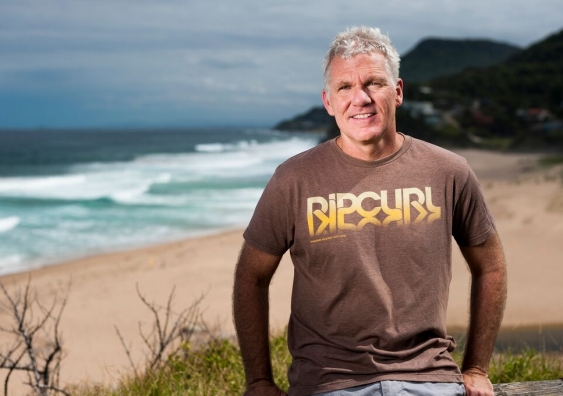

Co-editors of the 'Stories from the Field' collection, Prof. Rob Brander and Prof. Andy Short, have been conducting field experiments together since the early 1990s. Photo: Layla and Ivy Brander.

Improved technology – and the development of Occupational Health and Safety laws – have been the biggest changes to field research over the past 50 years, says Prof. Brander.

“In the early days, you were lucky if the instruments worked 30-50 per cent of the time,” he says. “Nowadays the success rate is often close to 100 per cent.”

Equipment has also become easier to set up and use, and the data they pull can be viewed and downloaded in real-time.

While new technology has changed the shape of fieldwork, Prof. Brander hopes the storytelling tradition continues.

“As a young scientist, hearing all these great stories became one of the best parts of fieldwork,” he says.

“Even today when scientists get together, they talk about their science, but invariably they start telling stories – like passing down tradition and folklore.

“While this issue focuses on coastal research, I hope that it inspires other field researchers – from all kinds of sciences – to capture their field history and stories, too.”

‘’ is available to access online for free.